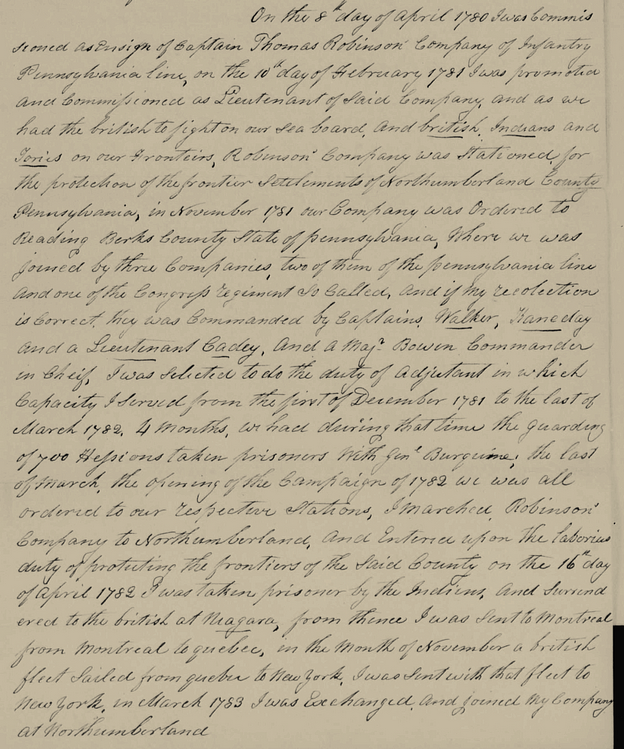

Moses' first-hand account of his Revolutionary War service, as detailed in his 1838 petition to Congress for his pension, is captured in this excerpt of the Otzinachson; Or, A History of The West Branch Valley of the Susquehanna, published in 1857.

Otzinachson

Or,

A History of The West Branch Valley

of The Susquehanna

By J. F. Meginness

Published By Henry B. Ashmead, Philadelphia, 1857

Nearly all the old people, yet living on the West Branch, are familiar with the names of Moses and Jacobus Van Campen. They were remarkable adventurers, as well as noted Indian killers, and distinguished themselves in many a well fought battle. Their services were very valuable in the protection of the frontiers.

In 1838, Major Moses Van Campen was living in the town of Dansville, NY, when he applied to the government for a pension. His petition to Congress is a very interesting document. The following extract relates to the Valley of the West Branch:

Extract of Moses Van Campen's 1838 Petition to Congress for Pension as a Veteran of the Continental Army."In February, 1781, I was promoted to a Lieutenancy, and entered upon the active duty of an officer by heading scouts; and as Capt. Robinson was no woodsman nor marksman, he preferred that I should encounter the danger and head the scouts. We kept up a constant chain of scouts around the frontier settlements, from the North to the West Branch of the Susquehanna by the way of the head waters of Little Fishing creek, Chilisquaque, Muncy, &c. In the spring of 1781 we built a fort on the widow McClure's plantation, called McClure's fort, where our provisions were stored. In the summer of 1781, a man was taken prisoner in Buffalo Valley, but made his escape. He came in and reported there were about 300 Indians on Sinnemahoning, hunting and laying in a store of provisions, and would make a descent on the frontiers; that they would divide into small parties, and attack the whole chain of the frontier at the same time, on the same day. Col. Hunter selected a company of five to reconnoitre, viz: Capt. Campbell, Peter and Michael Groves, Lieut. Cramer and myself. The party was called the Grove party. We carried with us three weeks' provisions, and proceeded up the West Branch with much caution and care. We reached the Sinnemahoning, but made no discovery but old tracks. We marched up the Sinnemahoning so far that we were satisfied it was a false report. We returned; and a little below the Sinnemahoning, near night, we discovered a smoke. We were confident it was a party of Indians, which we must have passed by, or they got there some other way. We discovered there was a large party—how many we could not tell—but prepared for the attack.

Extract of Moses Van Campen's 1838 Petition to Congress for Pension as a Veteran of the Continental Army."In February, 1781, I was promoted to a Lieutenancy, and entered upon the active duty of an officer by heading scouts; and as Capt. Robinson was no woodsman nor marksman, he preferred that I should encounter the danger and head the scouts. We kept up a constant chain of scouts around the frontier settlements, from the North to the West Branch of the Susquehanna by the way of the head waters of Little Fishing creek, Chilisquaque, Muncy, &c. In the spring of 1781 we built a fort on the widow McClure's plantation, called McClure's fort, where our provisions were stored. In the summer of 1781, a man was taken prisoner in Buffalo Valley, but made his escape. He came in and reported there were about 300 Indians on Sinnemahoning, hunting and laying in a store of provisions, and would make a descent on the frontiers; that they would divide into small parties, and attack the whole chain of the frontier at the same time, on the same day. Col. Hunter selected a company of five to reconnoitre, viz: Capt. Campbell, Peter and Michael Groves, Lieut. Cramer and myself. The party was called the Grove party. We carried with us three weeks' provisions, and proceeded up the West Branch with much caution and care. We reached the Sinnemahoning, but made no discovery but old tracks. We marched up the Sinnemahoning so far that we were satisfied it was a false report. We returned; and a little below the Sinnemahoning, near night, we discovered a smoke. We were confident it was a party of Indians, which we must have passed by, or they got there some other way. We discovered there was a large party—how many we could not tell—but prepared for the attack.

As soon as it was dark we new-primed our rifles, sharpened our flints, examined our tomahawk handles; and all being ready, we waited with great impatience till they all lay down. The time came, and with the utmost silence we advanced, trailed our rifles in one hand, and the tomahawk in the other. The night was warm : we found some of them rolled in their blankets a rod or two from their fires. Having got amongst them, we first handled our tomahawks. They rose like a dark cloud. We now fired our shots, and raised the waryell. They took to flight in the utmost confusion, but few taking time to pick up their rifles. We remained masters of the ground and all their plunder, and took several scalps. It was a party of 25 or 30, which had been as low down as Penn's creek, and had killed and scalped two or three families. We found several scalps of different ages which they had taken, and a large quantity of domestic cloth, which was carried to Northumberland and given to the distressed who had escaped the tomahawk and knife. In Dec. 1781, our Company was ordered to Lancaster. We descended the river in boats to Middletown, where our orders were countermanded, and we were ordered to Reading, where we were joined by a part of the third and fifth Pennsylvania regiments, and a Company of the Congress regiment. We took charge of the Hessians taken prisoners with Gen. Burgoyne. In the latter part of March, at the opening of the Campaign in 1782, we were ordered by Congress to our respective stations. I marched Robinson's Company to Northumberland, where Mr. Thomas Chambers joined us, who had been recently commissioned as an ensign of our Company. We halted at Northumberland two or three days for our men to wash and rest. From thence Ensign Chambers and myself were ordered to Muncy, Samuel Wallis' plantation, there to make a stand and re-build Fort Muncy, which had been destroyed by the enemy. We reached that station and built a small block house for the storage of our provisions. About the 10th or 11th of April, Capt. Robinson came on with Esquire Culbertson, James Dougherty, William McGrady, and a Mr. Barkley. I was ordered to select 20 or 25 men, with these gentlemen, and proceed up the West Branch to the Big Island, and thence up the Bald Eagle creek, to the place where a Mr. Culbertson had been killed. On the 15th of April, at night, we reached the place and encamped.

On the morning of the 16th we were attacked by 85 Indians. It was a hard fought battle. Esquire Culbertson and two others made their escape. I think we had nine killed, and the rest of us were made prisoners. We were stripped of all our clothing excepting our pantaloons. When they took off my shirt they discovered my commission. Our commissions were written on parchment, and carried in a silk case hung with a ribbon on our bosom. Several got hold of it; and one fellow cut the ribbon with his knife, and succeeded in obtaining it. They took us a little distance from the battle ground, and made the prisoners sit down in a small ring; the Indians forming another around us in close order, each with his rifle and tomahawk in his hand. They brought up five Indians we had killed and laid them within the circle. Each one reflected for himself—our time would probably be short; and respecting myself, looking back upon the year 1780, at the party I had killed, if I was discovered to be the person, my case would be a hard one. Their prophet, or chief warrior, made a speech. As I was informed afterwards by a British Lieutenant, who belonged to the party, he was consulting the Great Spirit what to do with the prisoners—whether to kill us on the spot, or spare our lives. He came to the conclusion that there had been blood enough shed; and as to the men they had lost, it was the fate of war, and we must be taken and adopted into the families of those whom we had killed. We were then divided amongst them, according to the number of fires. Packs were prepared for us, and they returned across the river, at Big Island, in bark canoes. They then made their way across hills, and came to Pine creek, above the first forks, which they followed up to the third fork, and took the most northerly branch to the head of it—and thence to the waters of the Genesee river."

Van Campen and his fellow-prisoners were marched through the Indian villages. Some were adopted, to make up the loss of those killed in the action. Van Campen passed through all their villages undiscovered; neither was it known he had been a prisoner before, and only effected his escape by killing the party, until he had been delivered up to the British, at Fort Niagara. As soon as his name was made known, it became public among the Indians. They immediately demanded him of the British officer, and offered a number of prisoners in exchange. The commander on the station sent forthwith an officer to examine him. He stated the facts to the officer concerning his killing the party of savages. The officer replied, that his case was desperate. Van Campen observed, that he considered himself a prisoner of war to the British; that he thought they possessed more honor than to deliver him up to the Indians to be burnt at the stake; and in case they did, they might depend upon retaliation in the life of one of their officers. The officer withdrew, but shortly returned, and informed him, that there remained no alternative for him to save his life, but to abandon the rebel cause, and join the British standard. A further inducement was offered, that he should hold the same rank in the British service that he now possessed. The answer of Van Campen was worthy the hero, and testified that the heart of the patriot never quailed under the most trying circumstances :”No, sir, no—my life belongs to my country; give me the stake, the tomahawk, or the scalping-knife, before I will dishonor the character of an American officer!"

In the month of March, 1783, Van Campen was exchanged by the British, and returned home. He was immediately ordered to take up arms again, which he did, and joined his company the same month at Northumberland. About that time Captain Robinson received orders to march with his company to Wyoming. Van Campen and Ensign Chambers accompanied them, and remained there till November of the same year, when the army was discharged, and they retired, poor and penniless, to the shades of private life.

A revised and expanded edition of similar title was published in 1889 including a sketch by the name of "Van Campen And His Thrilling Adventures."